You unfold like a flower, pt.2

At some point during one of my million pre-op appointments, I found myself sitting in my surgeon’s office listening to the PA explain to me how much everything was going to suck. She’d had the surgery, so I latched on to every word, hoping she’d reveal to me the secret of how not to have the surgery. Instead, I watched as she demonstrated to me how I would not be able to stand up fully for several weeks— “You’ll look kind of like a grandma,” she said, forming her hand into a loose fist meant to represent my future hunchback, “but over the first two weeks you’ll start to open up.” She slowly opened her hand, and I couldn’t help but picture the unfolding of a flower. I was heartened for a moment— I’m learning to love and not kill plants, a grace I would also like to extend to myself— and then I plummeted back into the morass of pre-surgery fear. Still, I keep this refrain in my head as I work to figure my way forward. For anyone reading about to undergo DIEP, or who is considering it, know that its extremely fucking hard (like, extremely), but I would do it again in a heartbeat. Its just important to know what you’re getting into- its ugly, its brutal, its beautiful, its absolutely survivable.

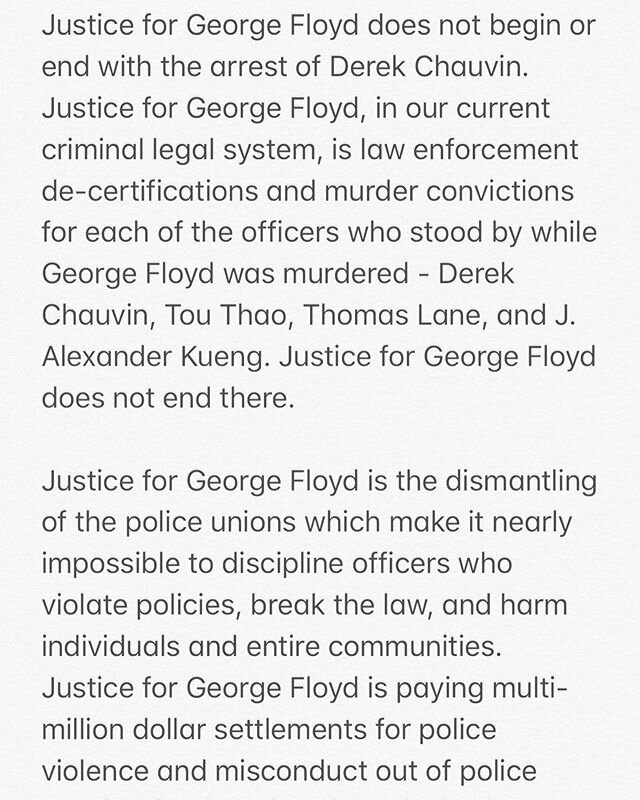

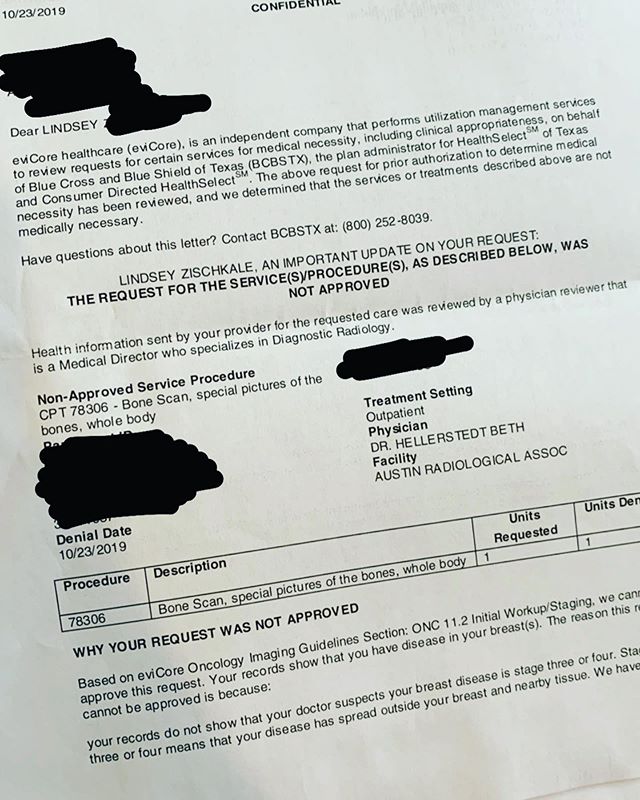

Wednesday is Breast Reconstruction Awareness Day (I am not pleased to reveal that I just realized the acronym is BRA…), so I figured what better time than to try and finish purging myself of the hospital experience. It occupies valuable brain space, displacing things like a stone in water, and I’d like to make some room.

I was not enthused by the idea of having a catheter, but it turns out NOT having one is even less fun. I had mine a day longer than usual, which I was extremely grateful for. Losing the catheter means getting out of bed, which means sitting up, which means walking, which then means getting BACK in bed. I went into DIEP knowing my surgeon ran a ‘boot camp’ (these were my other surgeon’s words), and I was ready to take on anything she threw at me— but holy fuck, it is so difficult to get out of bed after not moving for three days (two? Everything is a blur) and having a body-wide, open incision. My memories of the first time getting up are flashes— intermingled moments of fear and pain, teeth-gritting seconds where the only thing I could do was stare at the tile and rely on gravity to pull me forward. I was sporting some pretty interesting compression cuffs on my legs (sadly, not these) in order to prevent DVT, and getting up meant a long, complicated sequence of hooking and unhooking— unplugging my orange and white cuffs from the compressor, bringing my IV pole around from behind the bed, unplugging me from telemetry or whatever else, basically removing me from my robot docking station for a short moonwalk before hooking me back up to the charger. I can still feel the clamminess left behind by the compression cuffs, the cold sweatiness of hospital exertion.

The flow of memories is fuzzy, almost incomprehensible. My knowledge of time was based on what shift it was and when I was due for my next pain pill, so I don’t really remember when I got up for the first time. I think it was in the morning, and I wish I could remember which nurse was with me. Sitting up in bed may have involved the help of more than one nurse, it’s impossible to sit up on your own when you can’t engage your core. The process looked something like this:

I grasp one hand on to the bed rail while slowly rolling to my side and bringing my knees closer to my chest and down to the floor, like an excruciating but probably hilarious looking tuck-and-roll

At the same time, there is a nurse behind me helping push my back forward and keeping me from falling over. There is also a nurse in front of me to grab my hands and keep me from doing a very sad, very dangerous face plant (so mystery solved, I had two nurses!)

I slowly fling myself on to the waiting arms of the walker, and learn how far the 3-5 feet to the bathroom really can be

The first time they get you up, they want you to walk to the chair they have positioned a few feet away. Walking (shuffling) to this chair made me nauseous, sitting in the chair took a Herculean level of effort, and finding the strength to use ONLY my leg muscles to get up and propel me to the bathroom is somehow one of the hardest, most badass things I’ve ever done. I don’t think I’ve ever been more proud of my quads and hamstrings, and if I didn’t mumble something about doing squats to my nurses I certainly thought it. Recovery is a string of new, confusing, difficult, and horrible tasks— shadows of familiar actions that have suddenly become near impossible. Getting off the toilet? Very difficult! Getting out of the chair? You’d better gather your energy first. Walking? You’d best be patient, because 20 paces are going to feel like 20 miles.

If you were to ask me the most difficult thing about being in the hospital, I think I would probably have to point to getting back in bed. It is an exercise in faith, the world’s ugliest trust fall, and you have no choice but to do it. I hated getting back in bed, to the point where I agonized over whether to get up and go to the bathroom (protip: this honestly only makes you have to go to the bathroom more). Getting back in bed is close to the exact inverse of the getting out process, only with a lot more pain. I would position myself in front of the bed, facing out toward the bathroom and clutching my walker. Next, I would basically fall back into bed while one nurse lifted my legs and the other helped me roll on to my back. I feel an extreme fear and sadness even now, 12 weeks later. It really hurt to get into bed (try as you might, it’s impossible to not put at least a little stress on the incision), and it hurt even more knowing you were going to have to do it again in an hour. After a night of getting up every 20 minutes, I realized that I could sleep in the chair and we would all be happier. Aaron had been sleeping in the chair, and I remember being weirdly concerned that it was not ok for me to take the chair from him— in retrospect, sleeping in the hospital bed was probably more comfortable for him, a human with a working core and no incisions. All of that to say, if you can manage it, I highly recommend sleeping in the recliner!

After your first success getting into the chair, PT comes by to make you walk twice a day. Mornings are always going to be easier, and my first jaunt into the hallway was exhausting but also the first time I started to feel a glimmer of my personality returning. I picked a square on the floor in the hallway, apologized to the feet of a man who probably had to see my bare ass (lifting my head to see faces was too hard, and honestly the sight of the end of the hallway scared me), and scooted back around to the squeaky embrace of my plastic-covered chair. My breasts were still being checked every 15-30 minutes, I still didn’t really want to eat, hospital television was still bad (at some point I think I was unmoored from time, accompanied only by the horrors of the Amazing World of Gumball and the promise of another dose of anti-emetics), and I lived in fear of sneezing or coughing.

Before you are released to go home, you have to take a shower and show that you can shower yourself. My plastic surgeon kept me an extra day (I think to keep an eye on the rebel left breast), which meant I “got” to take two showers. Post-diep showers are not like regular showers. The night nurse comes in between 4 and 4:30am to start getting you ready for a 5am shower, and you start to ponder the cold, cruel facts of hospital towels. Showering is an even bigger production than walking— not only do you have to unhook from everything, you have to turn around in a tiny space and try and negotiate the small (read: mountainous) step up into the shower, and then figure out how you’re going to get back up. You’re also equipped with a drain belt, which is a glorified strip of velcro wrapped around your swollen, cylindrical stomach that the nurse attaches your drains to. The shower is the first time you see yourself naked and without gauze. It is jarring to look down and see angry, red incisions where your nipples used to be.

The nurse warns you ahead of time that water is going to get everywhere, and man is she not joking. Showering yourself post-diep really just means holding the shower head and aiming it at any part of your body you can think of, and slowly rubbing one arm pit with the rough, hospital-issued washcloth. You don’t stand on ceremony in the hospital, which means you spray water everywhere because you don’t have the dexterity to switch hands and aim the water away from the door. I was terrified of being touched, and I could not bear to touch my own breasts until I was weeks and weeks into recovery.

The first night I showered, I told the night nurse I was probably going home the next day. I sent her off at shift change saying I hoped I never saw her again (in the way hospital patients say goodbye to nurses, loaded with sarcasm, appreciation, and sadness), and I felt shame and disappointment when I had to stay— and shower— another day. Shower Round 2 was easier, but the drain belt remained a horrible, confining constant— one that would come home with me.

Discharge day is terrifying and exciting. At first I thought it meant I was going home to freedom, but really the bulk of recovery lies ahead of you. I put on quasi-human clothes for the first time in a week (an olive button down that I’d embroidered with “fuck cancer” on the pocket and FC on the lapels, as well as some extremely comfortable harem pants I would call an absolute must-buy), which was tricky. My arms, stomach, and legs were swollen and even the things I’d bought large did not want to fit. As my things were loaded up and my mom and Aaron went down to get the car, I lowered myself into the wheelchair and waited for the nurse to wheel me back down to the entrance. I had not been outside in five days, and since my gloomy ass had kept the blinds drawn, I had not seen the sun.

When my mom pulled up in her SUV, I started bawling. I was scared, and the few feet up into the seat looked impossible to navigate. The nurse was wonderful and consoled me, telling me everything was fine and that I was going to be able to get in the car. I remember panicking, thinking I wouldn’t be able to get in and that I would have to stay in the hospital forever. Obviously I made it out (or did I?!?!), but in the moment the fear was as real and vital as anything I’d ever felt. Somehow we got me up and into the car, strapped in with my five drains (I lost one before I left, which was a real point of pride), secure beneath my axilla-pillas, and I braced myself for the ride home.