Make mine a double? Notes on surgery

Does anyone remember Scribble Theatre on Sesame Street? Every time I try to explain to people how I’m feeling eight weeks out from surgery, all I can manage is “everything feels like a scribble.” Everything is this interconnected mishmash of emotions; I’m angry, I’m grateful, I’m terrified, I’m sometimes totally lost. I did not want to talk to many people after my diagnosis, and I felt like I had become some kind of dark Jesus— everyone wants to touch the hem of your sickly garments, give you sad looks, and speak to you in whispers. A lot of this feeling is obviously rooted in anger, and one of my continuing challenges has been figuring out how to allow people to love me. It is difficult to articulate the complex feelings that follow something like this— the flow of information is one of the only things you can control, and once it gets out it is hard not to feel like you are being used as tragedy porn. It is also, frankly, discomfiting to think someone’s friend’s uncle may be out there thinking about your mastectomy. I found myself wanting to tell everyone and no one; let’s all talk about my boobs, but don’t you dare look at them! I know I am putting out the “come here, go away!” message and it is an unfair thing to put on people, but when else can you get away with being unfair? Cancer is ugly, people are complex, and I am not someone who struggles in a graceful, instagram-friendly way. In my darker moments I feel like Persephone— this experience has snatched me, and I am in the middle of trying to figure out my way back out.

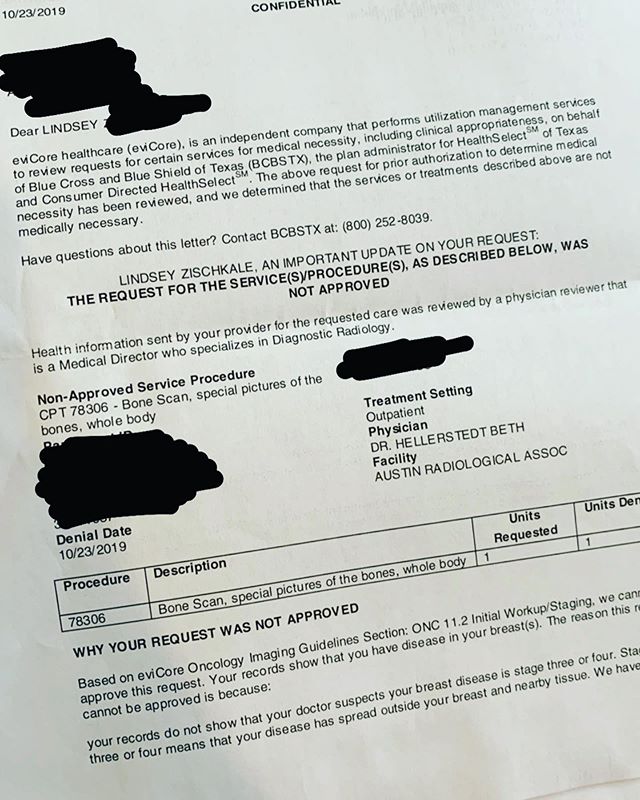

In the time since I last posted (apparently nearly 12 weeks ago, which feels like a lie), we made the decision to move forward with a bilateral mastectomy and DIEP flap reconstruction. I am a rip the bandaid off-type person, so I knew I wanted to get the surgery done as quickly as possible. You have to coordinate with a million people when you schedule surgery, so it can be similar to consulting a magic 8 ball— are the breast surgeon, plastic surgeon, anesthesiologist, and OR all available on the same day? Results unclear, ask again later. I was extra nervous trying to get everything scheduled, since my breast surgeon was very, VERY pregnant (as in, she had her baby a week after surgery) and I didn’t want to do the surgery with someone else. Luckily, we got July 22nd as a surgery date and I had a team of women I felt comfortable with— and, in my stronger moments, empowered by. I am continually grateful that I have been surrounded by my medical dream team, from the hospital to home. You’re going to see these people a lot, so be discerning with who you allow to take care of your body and don’t be afraid to go somewhere else.

Everyone’s experience is different, but I found it extremely challenging to function in the space between diagnosis and surgery. I would show up to the office but be completely unable to concentrate; cancer has an uncanny ability to transform itself into the most searing intrusive thoughts, and it is very difficult to answer constituent phone calls when you’re also imagining your own death. I’m not sure how high the pull bar in your bathroom should be, sir, but while I have you on the phone what do you know about post-surgical infections and wound care? I was very, very lucky to have an understanding office and enough sick time to work half days. For anyone about to go down a similar path, remember that taking care of yourself before surgery is just as important as after— you will want to go in to this process feeling as empowered, strong, and centered as possible to better situate you for an easier recovery. For awhile, I couldn’t muster the energy to figure out what that meant for me. I spent a lot of time shuffling around and sadly rattling my cancer chains like a ghostly victorian widow, usually complimented by a lot of long, sad baths where I’d bring in a book and then stare blankly at it (Dune is great for this). Cancer’s boyfriend is situational depression, and he will come in and try to sap the joy from the edges of your existence— sometimes you have to sit in that sadness, but sometimes you have to push through and do the things that made you happy until you start to feel again. My turning point in moving forward was getting my nails done; Meghann has always come through with pre-surgery masterpieces, and this time was no exception. Bon Voyage, Boobs was our theme, and the four hours we spent envisioning my boobs’ early retirement life recharged me in a way I didn’t think was possible.

Our post-surgery (Re)Birth of Venus nails were also crucial in a way that’s hard to describe— even though I’m not the one doing the work, the time spent creating these sets are like little battles where I get to beat the shit out of cancer, chronic illness, and trauma by turning it into something that makes me laugh instead of something constantly trying to bring me shame.

In probably the biggest instance of profligate spending (but with the least amount of regret!) in my life, we booked and planned a trip to Iceland in the span of five days. We were already intending on taking a trip to Bosnia, and I knew I needed to have a good-bye boobs world tour (Aaron took to calling it AreolaBorealis, which is even better). I am convinced those ten days were crucial to both me and Aaron being able to get through recovery— we had ten days together, away from doctors, pre-op appointments, and the claustrophobic walls of my own anxiety. I was able to steal hours at a time where I did not think about cancer, and driving through a place with so much elbow room gave my heart some space to breathe. Iceland feels like a suit of armor I put on before surgery, and the time spent there probably deserves its own post. If you can make it happen, bookend your treatment experience with time away. We will be spending the night in San Antonio the weekend before we return to work, and I think putting mental gaps between work, surgery, and return to work is invaluable. Taking a trip had the added bonus of giving me a bunch of pictures I could wildly demand doctors and nurses look at, which can serve as a nice distraction from the noise of the hospital.

As so often happens when I try to tell this story, I realize I’ve gone on and on without talking about the specifics of my experience. Pre-op and the five days in the PCU (where they check on you and your boobs every hour!) are indelibly drawn into my memory, but I experience it in pictures and still struggle to spit it out in words more artful than “my incision goes from hip to hip!” and “my husband had to wipe my ass!” I have had breast surgery before, so I was kind of prepared for what recovery was going to be like, but no one told me how important it was going to be to put away any and all pretense and get comfortable with basically everyone being in your business. I read a lot about having “t-rex arms” and having drains and the importance of having a recliner (probably the most important piece of advice I came across!), but it really wasn’t enough. Breast cancer is hard, surgery can feel damn near insurmountable, and maybe I need a little more time before my brain is ready to dive into the nitty gritty.